Their relationships might be close, the handshakes might have been firm, but President Volodymyr Zelensky had to roll his sleeves up during his trip to the US and Canada.

The latter was the easier end. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised to support Ukraine “for as long as it takes” against Russia’s invasion, and he has cross-party support in that endeavour.

America’s pockets are deeper, but its politics are far more complicated.

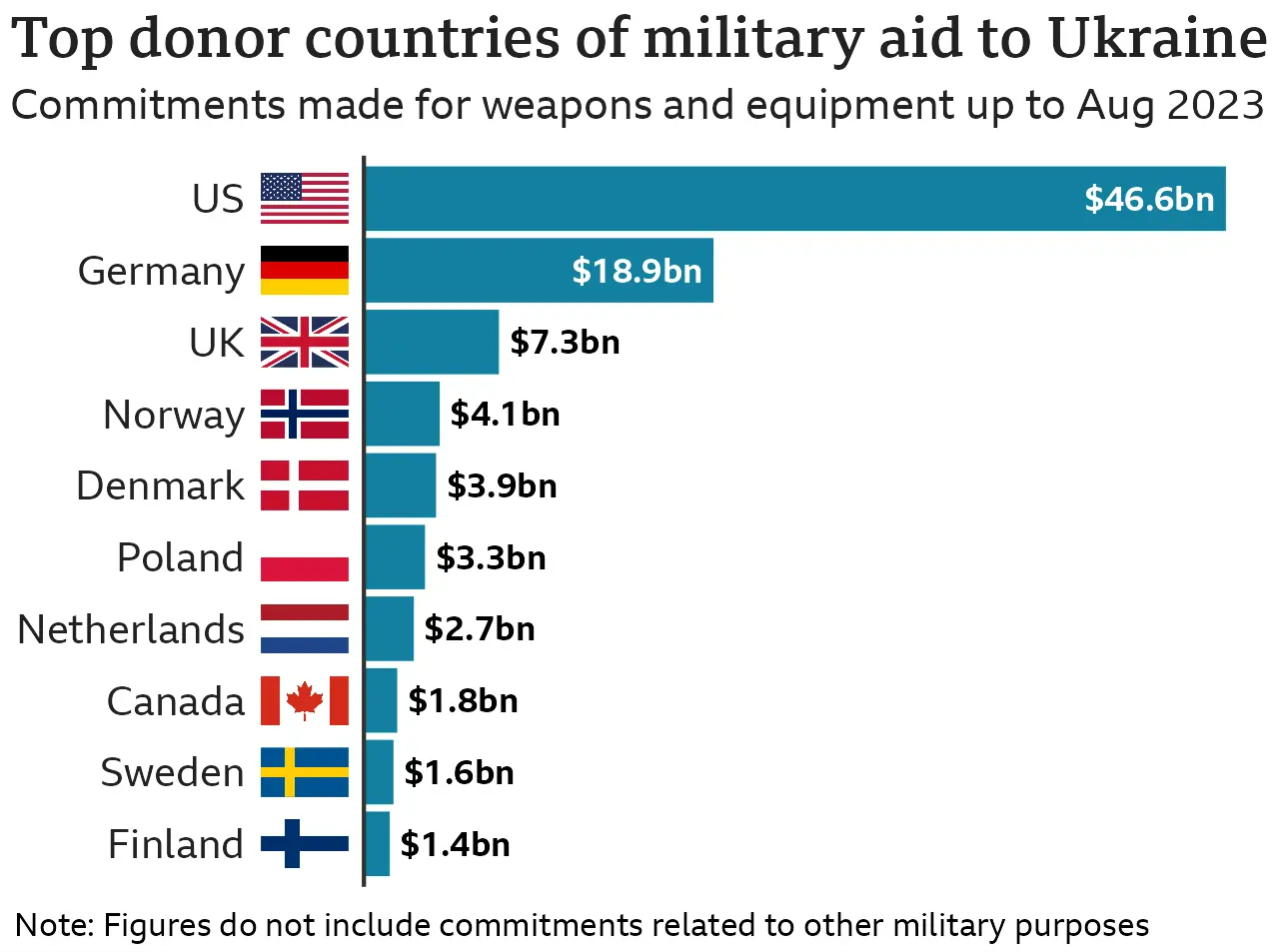

President Zelensky secured another $325m (£265m) military package from the White House, but it wasn’t the $24bn biggie he’d been hoping for.

That proposal is bogged down in Congress in a disagreement over budgets.

The difficulties do not stop there either.

Besides his counterpart Joe Biden, Ukraine’s leader also had meetings with Republican politicians who are struggling to contain the growing scepticism in their party.

“We are protecting the liberal world, that should resonate with Republicans,” a government adviser in Kyiv tells me.

“It was more difficult when the war started, because it was chaos,” he says.

“Now we can be more specific with our asks, as we know what our allies have and where they store it. Our president could be defence minister in a number of countries!”

Alas for Kyiv, he is not, and the political challenges are mounting.

“Why should Ukraine keep getting a blank cheque? What does a victory look like?”

These are both questions the Ukrainian leader has been trying to answer on the world stage.

And this is why he now seems to do more negotiating than campaigning – just to keep Western help coming in.

All in a week when Kyiv fell out with one of its most loyal allies Poland, in a row over Ukrainian grain.

A Polish ban on Ukrainian imports led to President Zelensky indirectly accusing Warsaw of “helping Russia”.

Let’s say that went down very badly in Poland, with President Andrzej Duda describing Ukraine as a “drowning person who could pull you down with it”.

The situation has since deescalated.

Even for a seasoned wartime leader, these are difficult diplomatic times.

Upcoming elections in partner countries such as Poland, Slovakia and the US are muddying the picture. Some candidates are prioritising domestic issues at the expense of military support for Ukraine.

“The need to balance military aid with the satisfaction of voters makes things really complicated,” explains Serhiy Gerasymchuk from the Ukrainian Prism foreign policy think tank.

“Ukraine has to weigh up promoting its interests, using all the possible tools, while taking into account the situations in partner countries and the EU. It is a challenge.”

These are the sort of democratic cycles Russia’s leader Vladimir Putin doesn’t need to worry about.

It is why Kyiv tries to portray this war as a fight not only for its sovereignty, but for democracy itself.

“The moral side of this war is huge,” says the adviser.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Ukraine, Russia, the US and UK agreed the Budapest Memorandum of 1994.

Ukraine surrendered the Soviet nuclear weapons left on its soil to Russia, in exchange for a pledge that its territorial integrity would be respected and defended by the other countries who signed.

Nine years of Russian aggression has made that agreement feel like a broken promise here.

Kyiv is also trying to play the longer game, by trying to better engage with countries like Brazil and South Africa, who have been apathetic towards Russia’s invasion.

It’s a strategy that has not brought immediate results.

“It is true we are dependent on frontline success,” says the Ukrainian government adviser.

He argues the media has oversimplified Ukraine’s counteroffensive by focusing too much on the theatre of the front line, where the gains have been marginal, and less on the substantial successes of missile strikes in Crimea and the targeting of Russian warships.

Ukraine has always claimed it “wont be rushed” in its counter offensive.

With the politics of this war increasingly connected to the fighting, that’s being tested more than ever.